The AV fistula had the origine of right internal iliac artery and drains off blood to right internal iliac vein.

DISCUSSION

Arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) of the female pelvis are

uncommon. These may either be congenital or acquired. Congenital pelvic AVMs

are characterised by a large number of arterial feeding branches. The arterial feeders are considered undifferentiated vascular structures

following arrested embryonic development at various stages [1]. Acquired pelvic

AVMs on the other hand, develop following spontaneous rupture of an atherosclerotic aneurysm into the adjacent veins or following

penetrating trauma (less than 20%), e.g. gunshot wound or stabbings, or after

lumbar disc surgery [2]. Therefore, acquired AVMs are most commonly arteriovenous fistulas (AVF). The AVFs are most commonly

aorto-caval fistula, followed by ilio-iliac [3] and aorto-iliac. However, the

etiology, clinical features, pathophysiology, principles of management and postoperative care for these fistulas are similar. Approximately

3 to 4% of all patients undergoing surgery for ruptured aorto-iliac aneurysm

are found to have AVF [3]. These carry a better prognosis than intraperitoneal,

retroperitoneal or enteric rupture of aorto-iliac aneurysms [5]. The disorder

has a marked male preponderance [4]. Other rarer causes of acquired AVFs include

Marfan’s syndrome, Ehler-Danlos syndrome, syphilis, Takayasu’s arteritis, invasion

by malignant tumour [2] and in some the cause is never ascertained.

Pelvic AVMs may manifest with symptoms of pain, haemorrhage,

haematuria, dyspareunia, or congestive heart failure, or symptoms secondary to

mass effect on adjacent pelvic structures. Acquired AVF, secondary to surgery

or trauma, tend to occur in younger patients as trauma or surgery tends to

affect younger patients. In contrast, spontaneous perforation of

atherosclerotic aneurysm into adjacent veins tends to occur in the older population.

Two large series report mean ages of 67.3 [6] and 69.7 years. The time of onset

of symptoms is usually earlier, from hours to weeks [3]. The initial diagnosis

is often that of an abdominal aortic aneurysm, AVF is often not suspected and

often the diagnosis is only made at surgery [5].

Iliac artery aneurysms and ilio-iliac fistulas are usually

associated with abdominal aortic aneurysm, as demonstrated in this case, though

they may occur as isolated entities. Rupture of atherosclerotic aneurysms into

the iliac vein may have three different clinical manifestations: sudden onset

of high output cardiac failure; pulsatile lower abdominal mass associated with bruit and thrill; or unilateral intermittent claudication or

venous congestion. Our patient presented with the first two clinical

manifestations and the tricuspid regurgitation was most likely secondary to

grossly dilated ventricle from high output cardiac failure.

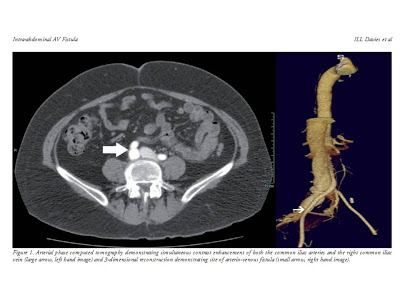

Ultrasound, CT or even MRI is almost always ordered for assessment of the abdominal/iliac aneurysms. Colour Doppler ultrasound has demonstrated the AV fistulas as areas of high velocity turbulent flow with aliasing of colour signal and also shows any associated thrombus at the aneurysm or fistula. Detection of ilio-iliac fistulas may however be difficult, as demonstrated by this case, as these tortuous and aneurysmal vessels lie deep within in the pelvis and obscured by overlying bowel gas. CT angiography is excellent in demonstrating the aneurysm and fistulous communications [6], especially with the advent of multi-detector CT and 3D software. Early contrast opacification of the iliac veins and inferior vena cava, and site of the fistula are clearly visualised.

Conventional angiography still remains the ‘gold standard’

for assessment of AVMs as well as assisting in assessing options for

endovascular management. Endovascular treatment has gained considerable favour in

the management of arteriovenous fistula especially for those with significant

high-risk comorbid factors. Options

available include percutaneous endovascular treatment with covered self-expanding

stent graft to cover the mouth of the fistula. However, this is not always

feasible due to the tortuous iliac vessels. Transcatheter embolisation with

coils or detachable balloons [7] is generally not recommended due to the large

size of the fistula, high flow and short neck.

Surgical options for AVF consist of endo-aneurysmal repair

of the fistula and prosthetic graft replacement of the aortoiliac aneurysm but

these are associated with high morbidity and mortality (approaching 60%) due to

the emergent nature of the procedure [4]. Thus early diagnosis

and appropriate management is of paramount importance. Unlike acquired AVFs, surgical

treatment of congenital AVMs is difficult due to the extensive nature and the

large number of dysplastic feeder vessels with the potential for exsanguinating

haemorrhage and damage to surrounding structures [8]. Accordingly, transcatheter embolisation has

become the treatment of choice [8]. Preoperative embolisation of AVMs has also

been used as an adjunct to decrease intraoperative blood loss. Small asymptomatic

AVMs that do not increase in size may be safely observed.

AVFs between major abdominal vessels are uncommon

complication of aortoiliac aneurysm. Ilio-iliac fistula in a female patient is

even rarer and associated with high morbidity and mortality especially if the

diagnosis is not suspected. In this patient, in the absence of history of

trauma or surgery and the presence of extensive aneurysmal disease involving

the aorta and iliac arteries, it is reasonable to believe that the AV fistula

was secondary to perforation of the aneurysmal right iliac artery into the

right iliac vein. In addition to the rapid onset, the presence of a single

communication and older age group lend more support to this diagnosis.

There has only been a single reported case in the literature

with an ilio-ilial fistula secondary to atherosclerotic disease [5]. In

addition the CT angiographic appearances of ilio-ilial AVF have not been described.

Spontaneous major

intra-abdominal arteriovenous fistulas: a report of several cases, Astarita D, Filippone DR, Cohn JD. Angiology1985, Sep;36(9):656-61.

Most major

intra-abdominal fistulas result from trauma or surgery. Spontaneous fistulas

are rare with less than 100 reported cases since 1831. From a review of

hospital records, five such spontaneous fistulas were identified among 215

cases of abdominal aortic aneurysm between 1975 and 1983. These cases are

presented and supplemented by 73 similar cases collected from a literature

review for discussion of the salient features of clinical presentation and

management of spontaneous major fistulas. Major intra-abdominal arteriovenous

fistulas usually present with a machinery bruit over a pulsatile mass, but may

present more subtly with pain and otherwise unexplained hematuria. Because

these fistulas lead to refractory heart failure, surgery should be expeditious.

Closure should be performed from within the aneurysm with arterial and

pulmonary artery pressure monitoring. Care must be taken to prevent pulmonary

embolization.