Abstract

Introduction: Ultrasonography is associated with a high

error rate in the evaluation of soft tissue masses. The purposes of this study

were to examine the nature of the diagnostic errors and to identify areas in

which reporting could be improved.

Methods: Patients who had soft tissue tumours and received ultrasonography

during a 10-year period (1999–2009) were identified from a local tumour registry.

The sonographic and pathological diagnoses were categorised as either ‘benign’

or ‘non-benign’. The accuracy of ultrasonography was assessed by correlating

the sonographic with the pathological diagnostic categories.

Recommendations from radiologists, where offered, were

assessed for their appropriateness in the context of the pathological diagnosis.

Results: One hundred seventy-five patients received

ultrasonography, of which 60 had ‘non-benign’ lesions and 115 had ‘benign’

lesions. Ultrasonography correctly diagnosed 35 and incorrectly diagnosed

seven of the 60 ‘non-benign’ cases, and did not suggest a diagnosis in 18

cases. Most of the diagnostic errors related to misdiagnosing soft tissue

tumours as haematomas (four out of seven). Recommendations for further

management were offered by the radiologists in 144 cases, of which 52 had ‘non-benign’

pathology.There were eight ‘non-benign’ cases where no recommendation

was offered, and the sonographic diagnosis was either incorrect or

unavailable.

Conclusions: Ultrasonography lacks accuracy in the

evaluation of soft tissue masses. Ongoing education is required to improve awareness

of the limitations with its use. These limitations should be highlighted

to the referrers, especially those who do not have specific training in this

area.

Key words: diagnostic error; haematoma; neoplasm, connective

and soft tissue; ultrasonography.

DISCUSSION

Ultrasonography lacks accuracy in the evaluation of soft tissue masses

due to the non-specific nature of many imaging findings. The present study has

reaffirmed our previous observations that ultrasonography has a high error rate

in distinguishing non-benign from benign lesions. Despite our earlier

experiences and the increased awareness of the limitations of ultrasonography,

no significant improvement in error rates was observed between the current and

the previous study periods.

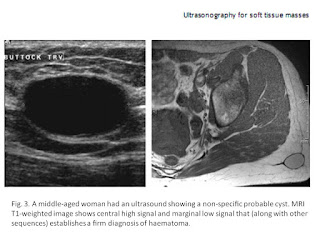

A common diagnostic error involves mistaking solid tumours for

haematomas, sometimes resulting in diagnostic delay and suboptimal management.

In a review of 31 cases of soft tissue tumours masquerading as haematoma, Ward et al. found that misdiagnosis was associated with diagnostic delays

averaging 6.7 months; furthermore,

neither ultrasonography nor magnetic resonance could reliably differentiate

soft tissue tumours and haematoma.[3] It may be useful to correlate

with clinical history such as recent trauma and examination findings such as

subcutaneous ecchymosis.[4] However, it is important to note

that a history of trauma may be incidental, and ecchymosis can also occur with

tumoural bleeding.[3]

Given these difficulties, it is not surprising that many radiologists

err on the side of caution when confronted with a soft tissue mass on

ultrasonography. Of the 115 patients with histologically benign lesions,

ultrasonography suggested a suspicious diagnosis or recommended further

evaluation in 92 cases (80%, positive likelihood ratio 1.1). A ‘positive’

ultrasonography result per se therefore adds little diagnostic value in the

evaluation of patients with soft tissue masses. On the other hand, one should

be cautious to assign a ‘negative’ result to a study without providing specific

guidance or recommendation. Notably, diagnostic delays have been observed in

false negative cases when such recommendation has not been explicitly made.

This is particularly relevant in our local practice, where non-specialists

(e.g. general practitioners) contribute up to 60% of the referrals for

ultrasonography examination for soft tissue masses. In these circumstances, a

short comment such as the following may help guide the referrers in appropriate

cases:

… The findings are non-specific. If the lesion does not resolve

rapidly, or if the radiological diagnosis does not fit the clinical picture, a

referral to a specialist surgeon is recommended and further imaging such as MRI

may be appropriate.

Despite its limitations, ultrasonography may serve specific roles in

the work-up of soft tissue masses. First, ultrasonography can confirm the

presence of a mass, which can sometimes be difficult to ascertain clinically.

Second, ultrasonography can differentiate cystic lesions from solid lesions.

Third, ultrasonography can often reliably diagnose lesions with certain

well-characterised sonographic features. For instance, a cyst adjacent to a

tendon may suggest a ganglion, and a superficial well-defined echogenic mass

may suggest a lipoma. It should be noted that the majority of these lesions are

satisfactorily managed in the community without being referred to the registry,

and are therefore excluded in this review. Fourth, ultrasonography may be used

to guide biopsy of the lesions. This is particularly valuable in targeted

biopsy of large, heterogeneous tumours.[5]

Ultrasonography has been utilised in tumour follow-up in the research

setting. It has been used to detect tumour recurrence[6, 7] and monitor regression of

tumour neovascularity induced by therapy for musculoskeletal sarcoma.[8] Ultrasonography may also be used

in conjunction with MRI when susceptibility artefacts from orthopaedic hardware

prevent evaluation of specific areas following surgery.[8] It has been suggested that

colour Doppler flow imaging and spectral wave analysis may allow assessment of

blood flow within soft tissue masses and, by inference, differentiate between

malignant and benign tumours.[9]

In summary, ultrasonography has specific roles in the evaluation of

soft tissue masses. However, aside from the recognisable entities of ganglion,

superficial lipoma and obvious peripheral nerve sheath tumour, ultrasonography

of soft tissue masses remains non-specific with respect to malignancy. Ongoing

education is prudent to improve our understanding of its limitations and

pitfalls. In addition, it may be important to highlight these limitations to

the referrers, especially if they have no specific training in the management

of soft tissue masses.